Some of the most important questions Christians need to wrestle with are about the Bible: what it is, where it came from, and whether or not we can trust it. Rather than letting fictitious books like The DaVinci Code inform our understanding of the Bible, we would do well to consider what the church has taught. The good news is, this is something that the church has spent a considerable amount of time and effort wrestling with, and there are answers to sufficiently handle any and all objections thrown at the Bible. The following series of short-answer questions are a brief introduction to issues of the New Testament Canon, the canonicity and reliability of the four Gospels, and how the issue of Canon applies to us today. Additionally, there are several recommended resources at the end of this article provided for further study.

1. What does the word “canon” refer to as it pertains to New Testament thought?

The word ‘canon’ (lit. “standard” or “rule”) refers to the collection of authoritative or normative writings that were deemed by the church to be inspired by God and therefore belonging to an exclusive set of Scriptures permanently given for the life of the church.[1] The New Testament Canon, containing a total of twenty-seven books, is received in addition to the thirty-nine books of the Old Testament to comprise the Evangelical Canon of Scripture.

2. Did the early church create the New Testament Canon?

The early church did not create the New Testament Canon; rather, it is more accurate to assert that the early church recognized the New Testament canon. God, having spoken through His Son, as well as his apostles and prophets, inspired the words of Scripture (2 Tim. 3:16; 2 Pet. 1:21). The early church regarded certain writings as divinely inspired and authoritative, established though various objective and rational criteria, and thus received them as Scripture. “The canonization of early Christian writings did not so much confer authority on them as recognize or ratify an authority that they had long enjoyed, making regulative what had previously been customary.”[2] In this way, the formation of the NT Canon served to clearly delineate the scope of those writings which had received broad recognition as authoritative Christian Scripture and thus also excluded others.[3]

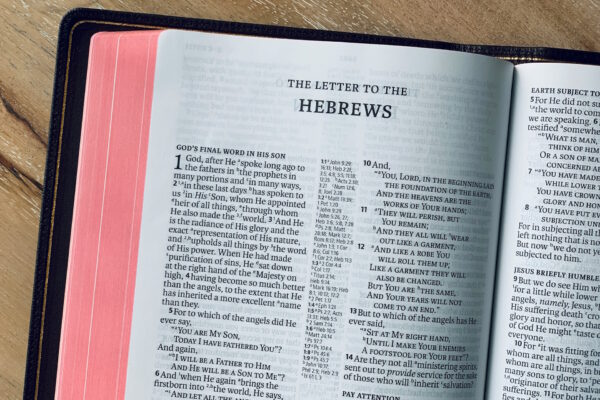

3. Where in the New Testament do we find references to the initial identification of other first-century writings as Scripture?

In 1 Timothy 5:18, the Apostle Paul writes: “For the Scripture says, ‘You shall not muzzle an ox when it treads out the grain,’ and, ‘The laborer deserves his wages.’” The second quotation is a reference to a saying of Jesus recorded in Luke 10:7. Paul is apparently equating Luke’s gospel with Scripture. In 2 Peter 3:15-16, speaking of the letters written by the Apostle Paul, Peter writes: “There are some things in them that are hard to understand, which the ignorant and unstable twist to their own destruction, as they do the other Scriptures.” Here, Peter is blatantly equating Paul’s epistles with other Scriptures, all of which are twisted by false teachers.

4. What three criteria were used to establish the Canon of the New Testament?

One criterion was apostolicity, which meant that the documents must have been written either directly by an apostle or indirectly through an associate of an apostle. Another criterion was catholicity, which meant that the documents must have been relevant to the whole church and had a history of longstanding, widespread, and well-established acceptance and use across Christian communities.[4] A third criterion was orthodoxy, which meant that the content of the documents in question must have been in line with the faith and practice of the church as generally understood from accepted apostolic teaching. It’s important to note that “the Christian community did not explicitly create these criteria as a set of standards by which it would canonize or reject specific books and letters”—they were principles that guided the Church, by divine Providence, in its investigation and recognition of Scripture.[5]

5. Approximately when was the Canon of the New Testament accepted?

The twenty-seven books that comprise the Canon of the New Testament were agreed upon by the majority of churches by the end of the fourth century. Athanasius, the bishop of Alexandria, set forth the first canon list naming these books as exclusively authoritative in his Thirty-Ninth Festal Letter, issued in 367 AD. [6] The church councils convening at Hippo in 393 and Carthage in 397 also promoted this same collection of books. “By the end of the fourth century there was a very broad, if not absolute, unanimity within the Christian community about the substance and shape of its canon of authoritative Scripture. This is remarkable insofar as there was never any official, ecumenically binding action of the ancient church that formalized this canon.”[7]

6. Approximately when were the four Gospels recognized as part of the New Testament Canon?

The four Gospels were recognized as canonical as early as the second century by means of significant literary, geographical, and artifactual attestation from the early church fathers and Christian communities. One of the several early church fathers who recognized a fourfold Gospel was Irenaeus of Lyons in the 180s. In his writings, he clearly recognized the Canonical Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John as being the only true and reliable Gospels, fully and exclusively authoritative, handed down to the church by the apostles.[8]

7. What literary attestation contributed to the early canonical recognition of the four gospels?

By the end of the second century, testimony to a fourfold Gospel converges from Christian communities across widely divergent geographical areas such as Alexandria, Antioch, Italy, and Gaul.[9] These Canonical Gospels are frequently used or named in the writings of several early church fathers such as Ignatius, Justin, Irenaeus, and Clement throughout the second century, being attested to far more than any other Gospel in circulation at that time.

8. What artifactual attestation contributed to the early canonical recognition of the four gospels?

A distinction between the popularity of the four Gospels recognized as Canonical as opposed to other written accounts can be observed in the physical format of the earliest manuscript fragments discovered. Of those in codex form (the most common book form used for Scriptural books), 39 instances of material from Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John can be found in 34 manuscript fragments, compared to only five fragments containing text from other Gospels. Additionally, multiple-Gospel codices produced within the first three centuries contain only combinations of the four Canonical Gospels, and two four-Gospel harmonies (by Theophilus and the Diatessaron byTatian) appeared as early as the mid-second century.

9: How might one respond to critics’ claims that more than just four Gospel accounts were written, such as the Gospel of Thomas or the Gospel of Judas?

First, while we obviously do not deny the existence of such Gospels, their existence—and even their occasional use by early ecclesiastical authors—does not necessarily imply that they should be included among the Canonical Gospels. Second, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John are the only Gospels we have that were written in first-century; the apocryphal gospels were not composed until after the first-century and thus could not have been written by an eyewitness to Jesus’ resurrection (failing the criterion of apostolicity). Third, some Gospel-like books, often promoted today as real rivals of the fourfold Gospel, were apparently never intended to even be in competition with other books recognized as Scripture.[10] Fourth, these noncanonical gospels were regularly subjected to “discriminative and selective procedures” by the early church fathers as a result of their deviation from orthodox Christian faith and practice; such procedures were not required when it came to the four Canonical Gospels, deemed instead to be “given by God in their fullness and entirety.”[11]

10. Why is the question of Canon important for believers to understand today?

Objections abound concerning the reliability of Scripture. Believers are often persecuted for determining their worldview from and basing their lives on the Bible. It is believed to be an outdated and nonsensical book, full of myths and legends, full of contradictions and discrepancies. Yet, we know first and foremost that the Canonical Scriptures are credible, reliable, and trustworthy because they were written by men carried along by the Holy Spirt (2 Pet. 1:21). God’s word is a firm foundation precisely because it is God’s word; Jesus himself validates the truth of Scripture by proclaiming that it “cannot be broken” (John 10:35). But such clear, objective, and historical evidence for how the Canon of Scripture came to be developed does help to add a further level of credibility to the Scriptures that we can use in our defense of the faith (1 Pet. 3:15) and in the gentle correction of our opponents (2 Tim. 2:25). While we must remember that “the natural person does not accept the things of the Spirit of God” (1 Cor. 2:14), we nevertheless can be confident in the Word of God that we hold in our hands today and provide an answer for the objections raised against the historical reliability of our Scriptures.

Recommended Resources on the Canon of Scripture

- The Origins of the New Testament Canon. This is a free course taught by renowned NT scholar, Michael Kruger. Additionally, you can pick up any of Dr. Kruger’s books on the Canon.

- Scribes and Scripture. Answers to Common Questions about the Writing, Copying, Canonizing, and Translating of the Bible

- One Holy Book, by Chad Spellman. An excellent short book for those wanting to learn what the Bible is, where it came from, why it matters, and whether or not we can trust it. You can also check out Chad Spellman on the Church Grammar podcast talking all things Canon.

- Can We Trust the Gospels, by Peter Williams. A case for the historical reliability and trustworthiness of the Gospels.

- A Peculiar Glory, by John Piper. An excellent and robust look at how the Christian Scriptures reveal their complete truthfulness.

Endnotes

- C. E. Hill, “Canon,” ed. Joel B. Green, Jeannine K. Brown, and Nicholas Perrin, Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels, Second Edition (Downers Grove, IL; Nottingham, England: IVP Academic; IVP, 2013), 101.

- H. Gamble, “Canonical Formation of the New Testament,” ed. Craig A. Evans and Stanley E. Porter, Dictionary of New Testament Background: A Compendium of Contemporary Biblical Scholarship (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2000), 192.

- Gamble, “Canonical Formation of the New Testament,” 184.

- Ibid., 193.

- Sylvie T. Raquel, “Canon, New Testament,” ed. John D. Barry et al., The Lexham Bible Dictionary (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2016).

- Gamble, “Canonical Formation of the New Testament,” 190.

- Ibid., 191.

- Hill, “Canon,” 101.

- Hill, “Canon,” 103.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.