One side-effect of our individualistic, anti-institutional age is that the church today often severs ties with its own history and scriptural traditions. What the church has always done and always believed—because the Bible tells us so—is set aside or “reinvented,” usually based on a particular church’s cultural milieu. In the case of American Christianity, churches tend to adopt visions of leadership held by fortune 500 companies. For example, rather than being led by plurality of elders, churches adopt deacon boards with CEOs at the helm. Instead of the pastor as shepherd of the flock, we have celebrity pastors who are far removed from their social media followers.

Unfortunately, the adoption of secular/cultural leadership structures can also lead to a similar adoption of values the world deems important for leadership, which are not always in accordance with Scripture. In Peter’s first epistle, we get a concise snapshot of what true pastoral ministry ought to look like. Peter gives us three ways pastors must follow Christ’s own example as they shepherd the flock of God.

Exhorting the Elders, Not the CEOs

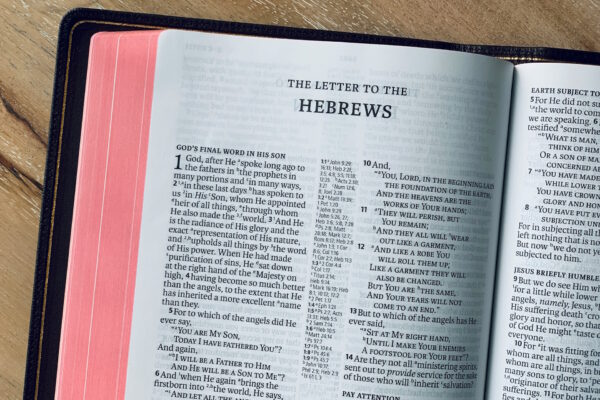

“So I exhort the elders among you, as a fellow elder and a witness of the sufferings of Christ, as well as a partaker in the glory that is going to be revealed: shepherd the flock of God that is among you, exercising oversight, not under compulsion, but willingly, as God would have you; not for shameful gain, but eagerly; not domineering over those in your charge, but being examples to the flock. And when the chief Shepherd appears, you will receive the unfading crown of glory.” (1 Peter 5:1–4)

The simple and straightforward charge given to elders is to “shepherd the flock of God, exercising oversight” (5:2). Rather than addressing apostles and CEOs, Peter addresses the elders of the churches receiving his letter (cf. Titus 1:5-9), similar to Paul’s farewell address to the Ephesian elders. That Peter elected to describe himself as a “fellow elder,” rather than apostle, would most likely have served to remind the elders that his charge to shepherd the flock (John 21:15-17) was their charge as well. The flock among them belongs to God, and they have been given the privilege and responsibility of caring for it until the chief Shepherd appears (5:4).

In this passage, Peter lists three contrasting pairs which explain how their task ought to be carried out. For readers familiar with the Old Testament, these instructions would be understood as an allusion to Ezekiel 34. The elders are not to be like the shepherds indicted by the prophet, who fed and cared for themselves, rather than the sheep (Ezek 34:3-8) and ruled over them with “force and harshness” (34:4). Rather, these instructions serve to set apart leaders in the church from those in the culture because these three descriptions of shepherding reflect Christ’s own example of care for his flock.

1. Not Under Compulsion, but Willingly

First, elders must not serve under compulsion, but willingly (5:2). This means not serving simply because they must, based on external or internal pressure, or because “someone’s gotta do it,” but because they have desired and freely chosen to shepherd God’s flock. David Wheaton writes that serving under compulsion suggests “a false sense of unworthiness, a reluctance for responsibility, or a desire to do no more than is absolutely necessary. Any one of these attitudes can lead to an unwillingness to take on the task or discharge it adequately.”[1] There must be a willingness and a desire to take on such valuable work (cf. 1 Tim 3:1).

In other words, the office of shepherd isn’t necessarily a “family business.” In our society, there is often pressure on children to follow in their parents’ footsteps by going into the same line of work, or for employees to step up when their bosses retire. When it comes to biblical eldership, no one should be pressured into the office against their will. This means pastor’s children should not be expected to carry on their father’s legacy simply because it “runs in the family.” Nor should faithful members of a church be required to “step up” and serve as pastor based on their faithfulness to a local congregation. Those coerced into serving will not be able to shepherd God’s flock the way God wants them to.

2. Not for Shameful Gain, but Eagerly

Second, elders must not serve for shameful gain, but eagerly (5:2; cf. 1 Tim 3:8; Titus 1:7). Throughout the NT, it is the false teachers who are said to have a love for money and status (cf. 2 Cor 2:17; 2 Pet 2:3, 14–15; Jude 11). But the desire to shepherd God’s flock must be based on a strong, whole-hearted desire without expected payment in return. As Mounce puts it, “elders should serve not for what they may get out of it, but eagerly for the good they can do.”[2]

In our day and age, it’s all too easy for church leaders to think they have this command checked off the list. However, the shameful gain Peter warns about is not just money, but also the desire for fame, a platform, and can even include a large social media following. Of course, this verse does not mean that fame and followers are necessarily wrong, but rather that these things should not be the goal of one’s calling to the pastorate. When it comes to biblical eldership and shepherding the flock, the goal the stewardship of the flock regardless of the “success” one might be given.

3. Not Domineering, but Being Examples

The third charge given to elder is to serve, not in a domineering manner, but by being examples to the flock (5:3). Their position of authority is not to oppress others, or to “lord over”, but to serve the spiritual needs of the flock. Just like husbands, elders are to use their authority to serve those in their care, not to push their own agendas. Like Christ, their lives must serve as an example of humility and sacrificial, self-giving love.

As churches continue to foster a celebrity culture, where pastors are viewed as CEOs and elevated as untouchable celebrities, we will continue hear story after story of pastors being fired for bullying and domineering their congregations. Problems of greed, selfishness, oppression, and shameful gain should not come as a surprise for churches bowing to the culture and not submitting to the lordship and example of Christ. Perhaps there is a correlation between the rise of celebrity culture and the downplaying and rejection of the gospel as central for all of church life and ministry?

Pastors, Shepherd the Flock

In his commentary on Peter’s first epistle, Paul Achtemeier provides a helpful overview of Peter’s charge to elders, worth quoting in full:

Christian leaders are, like good shepherds, to exercise their authority for the good of those entrusted to their care, not for their own satisfaction or enrichment. Christians are not the subjects of the elders, as is the case in the secular realm with leaders and subjects, but rather all Christians belong to God, and so the presbyters must carry out their duties as servants of God, not as lords of the Christians under their care. Arrogance toward other Christians and arbitrary exercise of power have no place in the leadership of the church, since those leaders also stand under God’s opposition to the arrogant but his graciousness to the humble (v. 5b).[3]

As the church recovers this historical and biblical model of leadership, the church will begin to look more like Christ, rather than the culture, and will receive the “unfading crown of glory” when Christ, the chief Shepherd appears at the end of the age.

[1] David H. Wheaton, “1 Peter,” in New Bible Commentary: 21st Century Edition, ed. D. A. Carson et al., 4th ed. (Leicester, England; Downers Grove, IL: Inter-Varsity Press, 1994), 1383.

[2] Robert H. Mounce, A Living Hope: A Commentary on 1 and 2 Peter, (Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock, 1982), 83

[3] Paul J. Achtemeier, 1 Peter: A Commentary on First Peter, ed. Eldon Jay Epp, Hermeneia—a Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1996), 329.