What is a Baptist church? For some, it’s a little country church that belongs to a denomination founded by John the Baptist. For others, it’s a church found in the south, filled with well-dressed parishioners wearing fancy hats and waving fans. Some, when they hear the word ‘Baptist,’ recall an experience in a Baptist church: old hymns, three-piece suits, wooden pews, a stern preacher, and potlucks.

Growing up in a Pentecostal church, the term had essentially become a synonym for a kind of church or Christian that was somehow ‘not-Spirit-filled’ (a tragically misguided sentiment; see Rom. 8:9-17; 1 Cor. 12:13; Eph. 1:13-14; 2:18). A Baptist was someone who cared more about the Holy Bible than the Holy Spirit. Moreover, if the congregation was not shouting “amen” loud enough or worshiping enthusiastically enough, the church was often charged with sounding “like a Baptist church.” Thus, it became as offensive to some as a swear word. The problem with these misconceptions and stereotypes is that they all fall miserably short of defining what a Baptist church is.

Different Denominations

Some clarification of terms is in order. The word ‘Baptist’ basically refers to a particular denomination within Protestant Christianity. A denomination, according to Merriam-Webster, is defined as “a religious organization whose congregations are united in their adherence to its beliefs and practices.” While many in the modern church of our anti-institutional age criticize and downplay the significance of denominations, quoting verses on nebulous church unity to support their view, John Hammett makes an important observation:

In the end, some type of denominational identity is unavoidable. In practice, every church has to answer certain questions. Should we baptize infants or believers only? Are we to be governed by a bishop, by a board, or by the congregation? What type of practices do we believe are appropriate for worship? Is each church connected to others, or does each church have a measure of autonomy? The answers provided to these questions and others like them align an individual and a church, to some degree, with a denomination, or at the least, place them within a denominational tradition.1John S. Hammett, Biblical Foundations for Baptist Churches: A Contemporary Ecclesiology, 20 (emphasis mine).

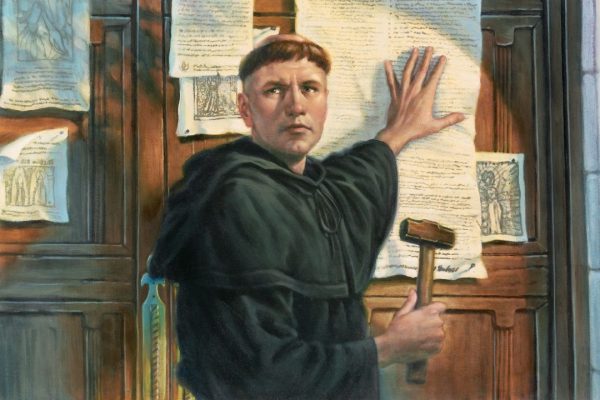

Denominations are not necessarily hindrances to church unity; they are simply the results of varying interpretations of Scripture. And ever since the Protestant Reformation, Christians “have not been able to reach agreement on the interpretation of Scripture on certain issues regarding what the church is and how it is to function.”2Ibid. For an excellent defense of why this is not necessarily a bad thing, see Kevin Vanhoozer, Biblical Authority After Babel. These are not issues essential to the being of the church but of its well-being, such as the mode and participants of the ordinances, church officers and government, membership practices, and so on.3For more on the marks of a true church, and the distinction between a church’s “being” and “well-being”, see Jason G. Duesing, “A Denomination Always for the Church: Ecclesiological Distinctives as a Basis for Confessional Cooperation in The SBC and the 21st Century”, edited by Jason K. Allen, 118-21.

A Baptist church, then, is a church that adheres to certain beliefs and practices; it is a church organized around a particular confession of faith and doctrinal practices. But what are those beliefs and practices? What distinctive doctrines qualify a church as being a Baptist church?

Distinctive Baptist Doctrines

The problem is that many—especially in Pentecostal and charismatic churches—fail to understand what those distinctive Baptist doctrines are. Historically, they have nothing to do with styles of music, spiritual gifts, Calvinism, Arminianism, or expressiveness in worship. There are both contemporary and charismatic Baptist churches today (such as The Village Church), and from the very beginning of the movement there have been Particular (Calvinist) Baptists and General (Arminian) Baptists. So, what is a Baptist church?

There are essentially five core beliefs central to Baptist identity. To begin, the distinctive doctrines of a Baptist church are mostly ecclesiological— that is, they pertain to the doctrine of the church. “Though none of these convictions is found only among Baptists, collectively they are defining convictions of Baptist Christianity. Wherever you find these distinctives affirmed, you find a ‘baptistic’ church, even if that congregation does not self-identify as ‘capital B’ Baptist, . . . and even claims to be non-denominational.”4Anthony L. Chute, Nathan A. Finn, Michael A. G. Haykin, The Baptist Story: From English Sect to Global Movement, 330-33. While an understanding of church history is crucial for providing the proper context in which these doctrines developed, and though many proof-texts could be cited for biblical support, I will keep their explanations brief.

1. Regenerate Church Membership

Baptists believe that, “A local church’s membership should be comprised only of individuals who provide credible evidence that they have repented of their sins and trusted in Jesus Christ as their Lord and Savior.”5Ibid., 330. This doctrine may seem patently obvious to some today. However, at a time when membership in the state church (i.e., the Church of Rome or the Church of England) was tied to one’s citizenship, this was a radical concept. And unlike our Presbyterian brothers and sisters—who see the children of believing parents as being members of the new covenant community and thus baptize them as infants—Baptists believe that membership in the local church is only for those who have made a personal confession of faith followed by believer’s baptism. For many, regenerate church membership is “the Baptist mark of the church.”6Hammett, Biblical Foundations for Baptist Churches, 81.

2. Believer’s Baptism

Baptists believe that, “Baptism should only be applied to individuals who give credible testimony of personal faith in Christ.”7Chute, et. al., The Baptist Story, 333-36. This distinctive naturally follows from and safeguards regenerate church membership; this is also where the term ‘Baptist’ comes from. Roman Catholic churches practiced infant baptism and, after the Reformation, Presbyterian and Anglican churches did as well (though Reformed churches did not uphold the doctrine of baptismal regeneration—the belief that baptism actually effects salvation). Baptists, however, maintained that the ordinance of baptism was only for those individuals who had made a credible profession of faith. Baptism by immersion, as they understood it, was tied to both the meaning (Rom. 6:3-5) and proclamation of the gospel (Matt. 28:18-20), following repentance and faith.

3. Congregational Polity

“Polity refers to a church’s basic structure and patterns of leadership. Congregational polity, or congregationalism, is the belief that local churches should be governed by their own membership. . . . [It] is simply living out the priesthood of all believers in the context of the local church.”8Ibid., 336-39. Regenerate church membership serves as the theological basis for congregational government, since each member of the church is ideally a Spirit-filled member of the true church of Jesus Christ. Congregational churches are first and foremost under Christ’s authority while led (not governed) by elders and deacons. “Each local church should be ruled by Jesus Christ, governed by its members, led by its pastors/elders, and served by its deacons.”9Ibid., 339. Congregationalism is one of three common forms of church government, along with Episcopalian and Presbyterian polities.

4. Local Church Autonomy

“Local church autonomy is the idea that every church is free to determine its own agenda apart from any external ecclesiastical coercion. . . . Positively stated, churches have the freedom to follow the Lord’s leading in their worship and witness.”10Ibid., 339-42. This distinctive is a corollary to congregational polity and is closely related to the others as well: “The whole congregation of regenerate saints takes ownership of the church’s ministry with the understanding that Christ alone is Lord of the church and his will is the standard by which the church’s faithfulness is measured.”11Ibid., 339-40. This does not mean, however, a local church cannot cooperate with other churches for the purpose of greater gospel ministry.

5. Religious Freedom

Religious freedom (also known as “liberty of conscience”) is the belief that, “every person is free to follow his conscience in religious matters without any human coercion.12Ibid., 342-44. Since the Bible teaches that all will stand before the judgment seat of God and give an account (Rom. 14:10, 12), no entity has the authority or the ability to come between a person and God. Historically, Baptists have held to the conviction that, “There ought to be no coercion in matters of faith, that there should be no established church, and that people ought to be free to hold matters of faith conviction with no fear of government reprisal.”13Chad Owen Brand and David E. Hankins, One Sacred Effort: The Cooperative Program of Southern Baptists, 21. One enters into the membership of a local church not by force or by birth but by a credible and voluntary profession of faith in the Lord Jesus Christ.

Summary

So, what is a Baptist church? It is a church where a congregation of baptized believers—under the Lordship of Christ and his word, associated by covenant in the faith and fellowship of the gospel, and led by elders and deacons—is the final authority in church governance. Though Baptist churches will differ on a variety of matters regarding styles of music, philosophies of ministry, the doctrines of grace, the miraculous gifts of the Spirit, and the elements of a worship service (and on and on the list goes), these five distinctives determine whether a church is baptistic or not. As it turns out, many who misunderstand the term ‘Baptist’ actually belong to churches that fully embrace these characteristic doctrines!

This by no means implies such persons must call themselves “Baptists” or change their church names to identify as such. However, a proper clarification of our terms—as well as a gracious and understanding disposition towards those with whom we may disagree—can serve as a crucial step in achieving greater unity in the body of Christ.

For Further Reading

- The Baptist Faith and Message 2000

- The Baptist Story: From English Sect to Global Movement, by Anthony L. Chute, Nathan A. Finn, Michael A. G. Haykin (Nashville, TN: B&H Academic, 2015).

- Biblical Foundations for Baptist Churches: A Contemporary Ecclesiology, by John S. Hammett (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Publications, 2005).

- Baptist Foundations: Church Government for an Anti-Institutional Age, edited by Mark Dever & Jonathan Leeman (Nashville, TN: B&H Publishing Group, 2015).

- Don’t Fire Your Church Members: The Case for Congregationalism, by Jonathan Leeman (Nashville, TN: B&H Academic, 2016).

- Going Public: Why Baptism is Required for Church Membership, by Bobby Jamieson (Nashville, TN: B&H Academic, 2015).

- Biblical Authority After Babel: Retrieving the Solas in the Spirit of Mere Protestant Christianity, by Kevin Vanhoozer, (Grand Rapids, MI; Brazo Press, 2016).