The view of God’s work of redemption through the lens of the Exodus and the repeated refrain heard throughout the pages of scripture point to a hope-filled future for the church. When we think of the Exodus, most of us would see in our mind’s eye a picture of Egypt, the Nile River, and a baby in a basket (Ex. 2:3). We might also envision a burning bush (Ex. 3:2), crazy plagues (Ex. 7:8-15-21), bloody doorposts (Ex. 12:7), and the institution of Passover (Ex.12:43-50). We would recall a pillar of fire and cloud (Ex. 13:17-22), the Red Sea (Ex. 14), a towering watery wall (Ex. 14:21), and a dry path through the water (Ex. 14:22). Some of us may think of Mount Sinai (Ex. 19), the tabernacle (Ex. 25:1-31:17), 40 years in the wilderness (Numbers), the promised land (Gen. 25:15; Ex. 3:17; Ex. 12:25; Ex. 32:13), and a grumbling people chosen by God. These pictures would summarize the Exodus, albeit in abbreviated form, but what we may not realize is that these pictures resound throughout the narrative of scripture from beginning to end; telling the story of the great redemptive work of God.

The Music of Exodus

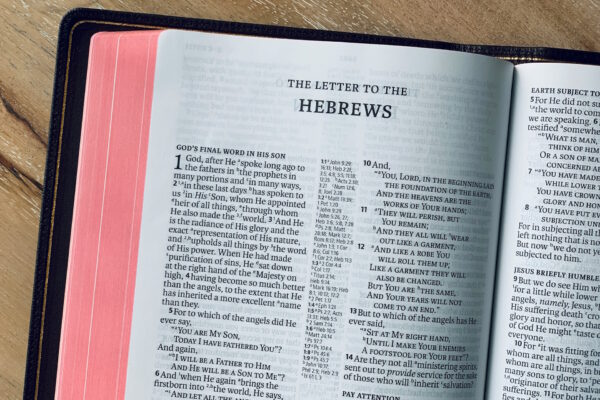

Alastair Roberts, in his book Echoes of Exodus, suggests that we think of recurring biblical themes surrounding the Exodus by a musical term – motif. We might describe the Bible as a symphony or love song, the Book of Genesis as an overture and the book of Revelation as a finale.1Alastair Roberts, Echoes of Exodus: Tracing Themes of Redemption through Scripture (Wheaton, IL; Crossway, 2018), 21. A musical motif is like a literary metaphor, directing the attention of the listener toward a particular theme, whether incredibly subtle or intentionally obvious, the point is to inform the listener of the plot, the story within a story, or the movement from tension to resolution. By taking a musical approach to reading scripture we begin to hear motifs and see patterns that help us understand the unity of scripture and the God who orchestrates from prelude to finale.

Exodus in Genesis

Before we are ever introduced to Moses or the burning bush, we see several Exodus motifs in the book of Genesis. The exile from the garden of Eden (Gen. 3:23) is like Israel’s journey into Egypt (Gen. 46-47). Just as God determines to judge the wicked and liberate the righteous by sending Noah and his family through the waters of judgement in an ark of pitch-coated wood (Gen. 6:14), God rescues the baby Moses through the water of the Nile, in a pitch-coated basket (Ex. 2:3). In the same way that Israel and Egypt both enter the Red Sea but only one emerges safe on the other side, so Noah’s family and the rest of the known world enter the floodwaters, but only one makes it out alive.2Roberts, Echoes of Exodus, 62.

Abram and Sarai, fleeing famine, leave the land of Canaan and descend into Egypt (Gen.12:10-20). Severe famine in Canaan would later lead Jacob and his twelve sons to descend into Egypt (Gen. 41-50). Even as Abram feared that he would be killed while his wife would be allowed to live, so the Egyptians would later plot to kill Israelite sons while keeping the daughters alive (Ex. 1:22). Just as the LORD had plagued the Pharaoh who had taken Abram’s wife, causing him to send them away, so too the Pharaoh of the exodus would be plagued until finally sending the Israelites out (Ex. 7-12).3L. Michael Morales, Exodus Old and New: A Biblical Theology of Redemption (Downers Grove, IL; IVP, 2020), 22.

Another Exodus story that appears in Genesis is seen in the life of Jacob. First, we see Jacob flee for his life from his homeland and seek refuge in the land of Haran (Gen. 27:43), which points back to Abraham’s Exodus to the same location (Gen. 12:5) and forward to Israel’s descent into Egypt. Jacob’s servitude to his Uncle Laban turns to forced labor (Gen. 29:27), just as Israel in the land of Egypt. In the same way Israel prospers and exits Egypt with riches, Jacob escapes his oppression with greatly increased possessions and riches (Gen. 31:1, 17). Jacob’s crossing of the Jabbok, a tributary of the Jordan River, introduces a motif that points forward to other passages through water (Exodus 14; Joshua 3; Matt. 3:13-17).

One last Exodus story in the book of Genesis surrounds the life of Joseph. His life and the life of Moses share many similarities. They both are set apart from their brothers at birth (Gen. 37:3; Ex. 2:1-10) and are rejected by them( Gen. 37:23, 28; Ex. 2:13,14); they both rescue entire nations from plagues/famine brought upon Egypt (Gen. 41:54; Ex. 13); both lead their family/nation out of impeding disaster in a land of abundance, but first lead them through a series of trials (Gen. 42:14, 25, 44:4-15, 45:1-9; Ex. 13 – Deut. 33); and they both die in a manner that points forward to the inheritance of the Promised Land (Gen. 50:24-26; Deut. 34).4Roberts, Echoes of Exodus, 78.

The Chorus Continues

We notice subtle clues in the Book of Ruth that bring to mind Exodus 19:4. “ You yourselves have seen what I did to the Egyptians, and how I bore you on eagles’ wings and brought you to myself.” In Ruth 2:12 and 3:9 we see Boaz and Ruth, respectively referencing the spreading of sheltering wings. “The God whose wingspan provides protection until the raging storm has passed by is present to bless Ruth and deliver her, as He was with Israel as they left Egypt.”5Roberts, Echoes of Exodus, 85.

In 1 Samuel we see the Exodus of the Ark of the Covenant as it is captured by the Philistines in battle (4:11) and descends into the temple of their god, Dagon (5:2). In the presence of Yahweh, Dagon falls to the ground repeatedly, and is ultimately crushed (5:4), just as Pharaoh is crushed by the waters of the Red Sea. This motif is heard again in the New Testament when the Son of God will save a nation by being captured (Matt. 26:47-56).

We see the Exodus motif in the lives of David and Solomon. Like Moses, David has few qualifications for his calling other than having shepherded sheep and having trust in the living God. “David, like Moses, is the prophetic leader who hosts God’s presence, draws Israel toward true worship, receives a covenant and prepares a house for the Lord to dwell in.”6Roberts, Echoes of Exodus, 96. Solomon, by building the temple, the dwelling place of God, in a way, brings an end of the Exodus from Egypt. This was the end goal of those that fled Pharaoh all those years before – a permanent house in which God’s glory resides. Solomon’s speech during the inaugural ceremony of the temple opens and closes with references to the historical exodus out of Egypt: “Since the day that I brought forth my people Israel out of Egypt” and “when he brought them forth from the land of Egypt” (1 Kings 8:16, 21).7L. Michael Morales, Exodus Old and New: A Biblical Theology of Redemption (Downers Grove, IL; IVP, 2020), 109.

As we read the book of Isaiah, we see the Exodus all over the place. This motif is more like the Chorus equivalent to Rich Mullins’ Awesome God as it echoes and resounds through the text – unmistakable. Isaiah 40-55 leaves the impression of being “more about the exodus than the Book of Exodus itself.”8John I. Durham, Isaiah 40-55: A New Creation, A New Exodus, A new Messiah (New York, Edwin Mellon, 1995), 52. We see a succinct summarization of the whole point of the Exodus in Isaiah 63:14, “So you led your people, to make for yourself a glorious name.”

When we look at the lives of Elijah and Elisha, we hear the familiar song of the Exodus. There are Jordan River crossings, mountain top encounters with the LORD (Sinai, Carmel), and leadership transfers that are similar. In many ways, Elijah and Elisha are the new Moses and Joshua. Just as Joshua and Elisha were ushered into ministry by Moses and Elijah at the Jordan River, another pair of prophets would meet at the Jordan river (Matt. 3:13-17). Yet unlike those before, this newly commissioned Prophet would bring to fruition the deliverance and redemption that Israel truly needed.

Jesus and The Exodus

From the opening chapters of the new testament, we are meant to hear the Exodus motif. In the scripture leading up to the birth of Jesus there are echoes of the Exodus in the names of the main characters; Joseph a faithful Israelite who has dreams, Miriam (Mary) a brave woman who protects the promised rescuer in childhood and who sings of God’s mighty act of deliverance.9Roberts, Echoes of Exodus, 125-126. Just as the LORD appeared to Moses the shepherd in the burning bush (Ex. 3), the heavenly host appeared to shepherds outside of Bethlehem (Luke 2:8-14). Like Pharaoh, Herod sought to kill all the baby boys (Ex. 1:16; Matt. 2:16). Just as the people of Israel go down to Egypt to escape the death of starvation from famine, Jesus goes down to Egypt to escape death. Though Israel escaped the oppressive foreign power by exiting Egypt, Jesus identifies with Israel, fulfilling the prophesy of Hosea by going down into Egypt and coming back out again (Matt. 2:13-15; Hosea 2:15).

Where Israel failed and was disobedient in the wilderness for 40 years (Numbers), Jesus was successful in obedience in the wilderness for 40 days (Matt. 4:1-11). We see the Exodus in the the account of the transfiguration in Matthew 17:1-13. Most notably, Moses and Elijah appear with the transfigured Son; Jesus’ face “shone like the sun” which reminds us of Moses’ shining face (Ex. 34:29-35); and Jesus explains his exodus to Peter, James, and John (Matt. 17:9-13).

Passover Blood, Pass Through the Water

If the theme of Exodus is a song, we have reached the crescendo or the big chorus after the bridge. The blood of the Passover lamb on the wooden doorpost was the substitutionary, sacrificial sign of the people of Israel in the historical Exodus (Ex. 12); Jesus is God’s Passover Lamb of the new Exodus (John 1:29, 36), whose bloody death on the wooden cross was the substitutionary sacrifice that would redeem the Israel of God. The Passover sacrifice was for the sake of Israel’s safe departure out of Egypt (death to the old life), and the Red Sea crossing symbolized Israels’ rebirth (or resurrection), with the ascent to Gods’ presence at Sinai corresponding to Jesus’ ascension.10L. Michael Morales, Exodus Old and New: A Biblical Theology of Redemption (Downers Grove, IL; IVP, 2020), 165. Through his resurrection and ascension, Jesus successfully completes his exodus out of old creation (Egypt) and enters into new creation glory (Promised Land). Just as Israel was baptized into Moses when they passed through the waters of the Red Sea (1 Cor. 10:2), Jesus baptizes God’s people with the Spirit of New Creation (John 1: 30-34).

Remembering and Proclaiming the Last Exodus

The Church remembers the Exodus when we participate in Baptism and the Lord’s Supper. In Baptism, we remember and celebrate the washing away of our old creation, the passing from death to life, the drowning of our enemies/sin in the floodwaters, and our new creation in Christ. In the Lord’s Supper, we remember how God has rescued us from slavery to sin and death through the blood of a Lamb uniting us to Christ.11Roberts, Echoes of Exodus, 155.

Every Exodus story since creation has fallen short of completion. Moses led Israel out of Egypt, but the entire generation died in the wilderness; Joshua brought the people into the Land, but the Canaanites remained; David purchased the Land for the temple, but sin prevented him from building it; Solomon constructed the temple, but idolatry continued; Jesus is victorious over death and ascends to glory, but much work is left for the church to complete in the power of the Spirit. As we await the grand finale, the return of our true and better Joshua, we stand on Jordan’s stormy banks, casting wishful eyes toward Canaan’s side. We look with hopeful anticipation for the last Exodus, when the Passover Lamb returns in glory to bring us safely to the other side.